Excuse some of the typos / spelling errors. This occasionally happens when looking at microfilm or a few other sites I enjoy

(NOTE: Article mentions EUGENE MARTIN AND JOHNNY GOSCH for fans of those crime cases)

The Des Moines Register

Des Moines, Iowa

02 Sep 1984, Sun • Page 1

Odyssey of Hope and Despair

By LARRY FRUHLING and BOB SHAW

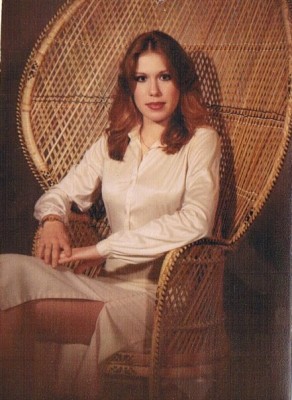

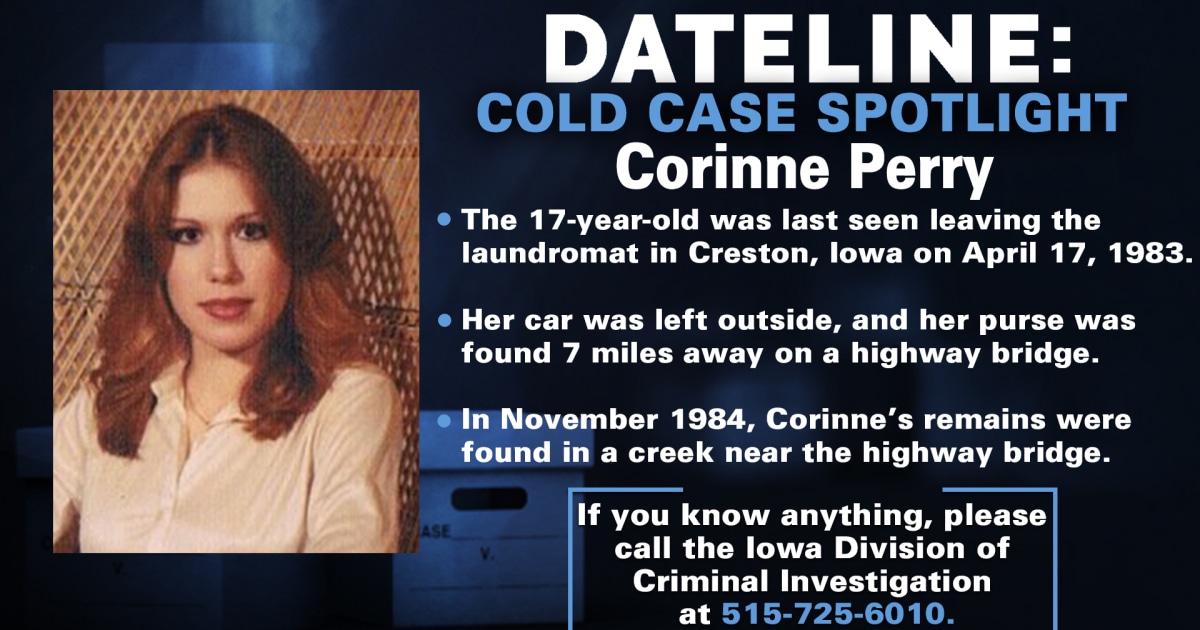

Several days after 14-year-old Eugene Martin vanished, Donald and Sue Martin, Eugene's father and stepmother, found themselves in a yellow and black sedan, riding with a stranger down the narrow road through a rural Polk County graveyard. The Martins were with a middle-aged, husky man who identified himself only as "Bernie." He had come to the door saying his psychic powers would lead the Martins to the graves of Eugene, Johnny Gosch, and three other young men. Bernie drove southeastward from the Martins' home at a maddeningly slow speed. Occasionally he pulled off the street and rubbed his eyes as though in deep concentration. The Martins became increasingly edgy as Bernie seemed to put himself in the place of Eugene, and then, as Eugene lapsed into unconsciousness, in the place of the boy's abductor. A week earlier, the Martins could in no way have imagined such a bizarre ride. Married only four months, they and the children that each brought to the newly formed household were busy adjusting to one another. Their main worry was that Donald was out of work and money was scarce. Now, Eugene had vanished from a street corner on Des Moines' south side in a haunting rerun of the disappearance of Johnny Gosch from a West Des Moines street corner nearly two years earlier. And the Martins' lives were cast upon an odyssey of grief, horror, faint hopes and crushing despair an all-too-familiar journey for two other Iowa families, those of the Gosch boy and of Corinne Perry of Cres-ton. Within hours of Eugene's disappearance, the Martins were under the magnifying lenses of detectives and reporters. Within days, they had learned of the slimy underworld of child *advertiser censored* and prostitution. Within two weeks, they had seen the story of Eugene's disappearance fade away under the dead weight of new no leads, no new information. Donald and Sue Martin, and Eugene's mother, Janice Martin, were the people most directly affected by Eugene's disappearance on Aug. 12 as he prepared to deliver the Des Moines Sunday Register to his 58 customers in a middle-class south side neighborhood. But hundreds of other lives were touched, too. An army of volunteers plastered the nation with "missing person" posters, searched woods and corn fields, and did whatever else they could to solve the mystery of Eugene Martin's disappearance. Attention was focused anew on the Gosch and Perry families and wounds that had never closed. Parents found fresh concerns for their own children. This story is about people cast into unfamiliar roles by the disappearances of three young people.

Continued from Page One is about fear, hope and anger, and most of all about the unbearable suspense of three mysteries jthat have eluded a conclusion, one for two years, one for 17 months, and one for three agonizing weeks. Almost four hours went by before "Bernie," the psychic, had made his way with Don and Sue Martin to Avon Cemetery southeast of the Des Moines city limits a trip of no more than six miles from the Martins' house at 1905 Frazier Ave. Inside the cemetery, Bernie said it had grown too dark to find the graves. By then, the Martins were frightened and only too happy to call off the whole thing. "Not too many people scare me, but he had my skin crawling," Donald Martin said later. The Martins, a friend and a policeman went back the next day to search the cemetery. They found nothing and they heard no more from Bernie. Dec. 18-21, 1983: "God, how appalling to have to sell a piece of chocolate to find our boy. . . . Christie and Tammy are working Locust Street Mall selling candy. A lady walks up to Christie, spits on her and says, 'I wouldn't help your mother find that kid if it was the last thing I ever did.' Our daughter fell completely apart. That will be the last time any of our children will participate in any fund-raiser." Noreen Gosch, whose son Johnny vanished Sept. 5, 1982, while on his Des Moines Sunday Register route in West Des Moines, wrote those words in her diary. Janice Martin sits in her darkened apartment by a telephone, brown vial of tranquilizers by her elbow and a cup of coffee in her hand. "I drink three or four pots a day," she says in a thin, brittle voice. "It doesn't bother me, because I take my pills." Since her son, Eugene, vanished three weeks ago, her life has been reduced to waiting by the phone and occasionally searching fields and ditches with teams of volunteers. "They let me go sometimes. But I was told that I shouldn't really come along, because if I was with them and they found something "First you get scared, then hurt, then angry, then you blow a fuse, then you start all over again," she says. "My mind isn't there. I'm in and out." Until Eugene vanished, she worked part-time, supporting three children. "I'm a bartender. A lot of people say, 'Yup! See?' when they hear that," she says, describing the telephoned accusations that she had failed as a mother. "It isn't true, but it still hurts. I've had six or seven calls saying things like, 'If Gene had been home where he belongs, he'd be there today.' I didn't know how many strange people there were." Martin recalls the Sunday Eugene disappeared. For her, the night before had been a late one at the Sunrise Tap, a fixture at East Forty-second Street and Easton Boulevard for as long as anyone can remember. She'd had to close the bar and did not get to sleep until 3 a.m. Four hours later, the phone jangled her awake. It was her sister-in-law, Linda Martin, telling her Eugene had vanished while on his paper route. He had been staying at the south side home of his father, Don Martin, whom Martin had divorced two years before. "It took a couple of seconds for it to connect," Martin says. "I knew he didn't ran away. I talked to him that Tuesday. His birthday was coming up, and he told me he wanted a ghetto blaster like his brother's." As the investigation ground into its third week, Martin says, "Everyone has their theories, but no cold, hard facts. I guess you could say there is no trace. I wonder where he is at, what he is doing, whether he is asking for me and his dad." Two of Martin's uncles from Saylor-ville, Roger Blanchard and Bob Walker, drop by to check on Martin. They have been searching for Gene, sweating through weeds for hours, and they are bushed. Walker, a likeable galumph of a man, plops onto a sofa. "Yup, every year the kooks come out of the woodwork, and them paperboys are easy targets that early in the morning." At the Sunrise Tap, a Tupperware box full of collected money sits on the bar. A note taped to it reads: "Janice You have our Prayers also our Love and Most of all our support. Your friends at Sunrise." Everyone there is fiercely protective of Martin. Between serving Bud-weisers, owner Darlene McElwee shook her head: "It's awful hard to lose a child. But to lose one with no finality to it is something else. People go down the street looking both ways now. Johnny Gosch upset them. This one made them aware." To a reporter, one bar patron says: "Hey. Don't write anything to hurt her, OK?" More than 400 people sit in the spacious sanctuary of the First Assembly of God Church on Merle Hay Road in Des Moines for a terror-filled, two-hour-and-20-minute program on sexual abuse and murder of children. One speaker, Bob Currie, had three children who were among many students allegedly molested by the owners and staff of the Virginia McMartin Pre-School in Manhattan Beach, Calif., Lot Angeles suburb. Currie tells of watching a videotape in which a psychologist interviews Currie's son, now S years old, about the boy's experiences at the school. At v y r 1 4, Eagene Martin Leads have dwindled Johnny Gosch Nothinybut dead ends Corinne Perry Disappeared in Creston the end of the interview, the child vents his rage by thrashing the puppets the psychologist has used as go-betweens for the questions and answers. "It looked like an Alfred Hitchcock movie" one in which his own son was the featured actor, Currie tells the crowd. A film made by the Minnesota-based Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children opens with a news conference called by two officials of the North American ManBoy Love Association. One of the lisping officials is saying that young boys and girls should be allowed to engage in sex acts without their parents' consent. It is, he says, a matter of "civil rights." He refuses to say how young is too young. The film ends with the heartbreaking funeral of Adam Walsh. Adam was 6 years old when he was abducted from a Fort Lauderdale, Fla., shopping center in 1981. His head was found later in a canal. Many people are weeping when the movie ends. When the lights go on again, there is an appeal for money to help find Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin, and about $1,000 is dropped in the blue bags the ushers have circulated through the pews. The crowd's most enthusiastic applause is delivered for Noreen Gosch when she suggests reinstating the death penalty in Iowa for certain sexual offenses against children. "These pedophiles their desires never die," she says. The implication is clear: Even if their desires will not die, pedophiles adults with a sexual attraction for children will. After the meeting, Denise lies, 33, of Clive, explains why she came: "I have a 12-year-old son. The bottom line with me is, I'm scared. It's as simple as that." At the regular Corinne Perry Support Group meeting in Creston, the mood is brisk and businesslike. Since April 17, 1983, when Corinne Perry, 17, vanished after washing her clothes at the B. D. Highlander Laundromat, the group has brainstormed i 5 ( 1 Jf. V ' I ; 4 ? 01 rs!t Janice Martin "My minp isn't there . . i '!: lit. t- iStf&xA tfs4 jLAa iv y.x- The streetcorners where Eugene Martin, twice monthly in the basement of the First Congregational United Chur ch of Christ about how to find her. "Where are we on the fliers? Did we decide not to do the airports?" asks the Rev. Lyle Kuehl, the church pastor. He looks at the 13 people huddled around a folding table, then at Cor-inne's mother, Barbara. "Well, how many do we send to each airport?" she asks. "To Joplin we sent 10. How many to Kansas City? Denver?" Don Perry, Corinne's father, scans the table, cluttered with posters and pamphlets about Corinne and with magazines about missing children. The Rev. Dolores Docnch of nearby Cromwell gets an idea. She has recently married a couple in New York City, and the groom is a mechanic for a bus company. "Would it be advantageous to see if he knows about the ad rates for the posters in those buses?" she asks. Everyone nods. Corinne Perry and the two paperboys are the only victims of possible abductions in the state who are not accounted for, officials say. And as in the other cases, friends and strangers have instinctively gathered around the grieving parents. "I'd lose my mind without these people," Corinne's mother says. Support groups bake hot dishes. They lick stamps and call congressmen. They plaster posters in truck stops on their vacations. They cry with the families. But above all, support groups keep hope alive. Corinne's sister, Letitia, 21, keeps a plain, spiral-ring notebook to record every personal event that would be of interest to Corinne. The most recent entry is, "Lloyd and Laura moved to Council Bluffs." Letitia says, "I put in births, deaths, divorces, anything she will need to know when she gets back." Dennis Gregory Whelan, private detective, with offices on the ground floor of an apartment building on the west side of Omaha, Neb., worked on the Johnny Gosch case about eight months before giving it up in exhaustion and frustration. Although he is no longer employed Stanley Johnson Helped to search T r i 1 I f f iU ft r v - - ;,:.,' ' " J ' 1 :;';".., x V j i & t-A. -sJ top, and Johnny Gosch, bottom, were by the boy's parents, a color photograph of Johnny is prominent on his office wall, along with smaller, black and white pictures of about 40 other children for whom Whelan has searched Some were returned to their parents dead, some alive. In Whelan's front office is a large United States map on which are pinned 62 small red flags, one for each reported sighting of Johnny The markers span the msp from Fargo, N.D., to Mc Allen, Texas, and from San-Francisco, Calif , to Taunton, Mass. Whelan is one of many investigators, private arid official, who have been frustrated in their search for Johnny Gosch. They are well aware that they have so far failed in what they are paid to do. "I think everyone would take it personally to a degree," says Lt. Lyle Mc-Kinney of the West Des Moines Police Department, whose full-time assignment for nearly two yeai-s has been to find Johnny Gosch. McKinney started on the case Sept. 27, 1982, when he returned from a police-training school in Virginia. "You, you're given a job to do, and you take pride in doing the job as well as you can and reaching some type of successful conclusion," says McKinney. The Gosch case occupies four drawers in McKinney's filing cabinets. His carefully lettered notes fill a handful of battered, much-used notebooks. Thousands of tips and leads have come to nothing. "I don't know where Johnny Gosch is," McKinney says. "I don't have any idea." The Gosch case still brings five, six, seven calls a week from people wanting or offering information, McKinney says. "One of the things that keeps rne interested is that I have a boy that age who had a paper route at that time and was delivering papers on Ashworth Road that morning," says McKinney, who, unlike many other law officers, has retained the Gosches' respect. Detective Whelan, who looks like he has been down a lot of reads in his 49 years, tells of many twists arid turns in the Gosch investigation all leading to dead ends. Nothing came of Whelan's importing of a young man, a homosexual, from Omaha to infiltrate Des Moines' homosexual community in hopes of a lead to Johnny's disappearance. Nothing came of Whelan's trip to New England to look through thousands of child-*advertiser censored* pictures seized in a raid. Nothing came of the investigation of a Texas trucker who claimed to have picked up Johnny in West Des Moines and driven him as far west as Atlantic. "If he is alive, he's not in the United States," Whelan says. "And now, with the second one the disappearance of Eugene Martin), I'm not even sure he's alive." Eugene Martin has been missing without a trace for six days when Stanley C. Joiuison, a 63-year-old re Uhv . i - 4 - ' V' - .r. v 5 r frVN if, wt ,&sSj&&MfcA3HaW last seen. tired insurance salesman, drives up to a large cornfield south of Ankeny to help find him. Johnson and about 35 others who had answered the Des Moines Police Department plea for volunteers fight their way through the dirty, dense rows of 7-foot-tall corn for several hours in the suffocating humidity, sharp corn leaves slapping their faces. Their instructions were deliver ed at 8.30 a.m. by a bleary-eyed policeman, Richard Davis, who had been among the officers who went through part of the field from midnight until 3:30 the same morning, reportedly on the advice of a psychic. Davis tells the volunteers they are looking for a shirt, blue jeans and size 8 tennis shoes the Martin boy was wearing when he disappeared, or for Martin's body. "If you find anything, don't touch it," Davis instructs. "Just stop and call for an officer. We don't want any evidence disturbed." Stanley C. Johnson fumbled for words to explain why he had joined the search. For one thing, he regretted not having helped look for Johnny Gosch. "The fact that this has happened again makes you even more concerned," he says. He adds: "We've been praying for them, but sometimes praying is not enouph. We are God's hands and voice and feet. We need to pitch in sometimes. I'm not very good at expressing myself when it comes to something like this, but that's the way I feel." The search is fruitless. Two hundred and fifty miles away, Corbyn Jacobs, chief of the 16-mem-ber Palmyra, Mo., Volunteer Fire Department, requests missing-persons pesters of the Martin and Gosch boys. Jacobs, 62, and the "other boys" on the fire department soon have plastered western Illinois and eastern Missouri with pictures of Martin and Gosch. A few weeks before Eugene Martin disappeared, a Burlington Northern freight train went by Jacobs' house in Palmyra, a town of 3,644 residents. He had seen a young boy riding on a rail car with a dog. He called a Burlington Northern dispatcher about the boy and was told a railroad detective would get in touch right away. "Nobody called me back about that lad," Jacobs says.- "That's one of the things that touched me off about those Des Moines boys. Nobody seemed to care. That boy on the train had to belong to somebody, too. He had to be a good kid; he had his dog with him." The 300 posters distributed by Jacobs and his volunteer firemen are among 148,000 that the Des Moines Register and Tribune Company ordered to fill requests. Thousands of additional posters were provided by other printers. Noreen Gosch trembled as she inched her car down Forest Avenue past Thirteenth Street, peering through the dark for the fire hydrant where she was supposed to drop the 120,000 ransom. Beside ber, in a paper bag, was a "ransom" of two pieces of wood. J - - M! 1 :;.V . tf, '() 5 Crouched behind her in the back seat was her private detective, gun drawn. She thought of what it would be like get the severed hand of her son in the mail. Hours before, a deep voice on the telephone had threatened to arrange just that. She pulled over, stepped in front of the headlights and threw the bag down. Several hours later, police officers returned the bag to the Gosches. No one had picked it up, and there was still no Johnny. "I never was so scared in all my life," she said later, describing the false alarm that happened Oct. 13, 1982. She has since endured worse. Like an angry mother grizzly, Noreen Gosch has snarled and snapped and fought. She and husband John have prodded, begged, offended, hustled, stepped on toes and frazzled nerves. They have endured insults, accusations and a procession of swooning psychics. They have been dogged and even outrageous. But no one can talk to the couple very long without realizing they would run naked down the MacVicar Freeway if it would help them find Johnny. "We still walk by his bedroom every day," said the mother. Noreen Gosch is a phenomenon. Des Moines parents who have never met her refer to "Noreen" in conversations. She and John have appeared on the "Today" show, changed Iowa's kidnapping laws and supervised distribution of tens of thousands of "Find Johnny Gosch" posters. "Noreen should run for president," declared one woman in her neighborhood. "She gets things done." After the Sept. 5, 1982, disappearance, Noreen Gosch got some advice, she said: "A very wise man told me, 'Whatever you do, keep yourself under control. Make a plea for your son's life. But don't break down because if you do, they'll use your story maybe once or twice, and then it's done. You are in for a long search, and it's going to be up to you to keep the story going.'" . That she has done. And parents whose children have vanished since . Johnny acknowledge a debt to her. "There wouldn't be such a big deal about Eugene Martin if Noreen hadn't made such a stink," said a mother in a supermarket checkout line. By maximizing exposure to the public, the Gosches have opened them- ' selves to attack. Noreen said that at one of many of ; her presentations, "The publisher of a small newspaper said, 'I don't think you ever had a son named Johnny. I think you are doing this for the money, the power and the glory.' I told him, 'I hope they get your kid next' I don't have to take that I am arrogant now." t Dallas Davis, neighbor and close friend, snapped: "Most of the com- 1 ments I have heard from what I will ' call extremely ignorant people are things like 'Noreen appeared in full makeup,' or 'Noreen appeared on TV with her fingernails painted.' Who re- MISSING : Please turn to Page 7 A